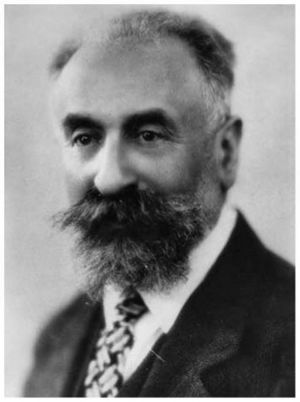

Marcel Mauss

| Marcel Mauss | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Born | 1872 | ||||

| Died | 1950 | ||||

| Residence | 2 Rue Bruller, Paris XIVe | ||||

| Occupation | sociologist | ||||

| |||||

Contents

Notes

Office Notes

House Notes

1925.11.17 The following were suggested as Honorary Fellows: Dr Mauss, Dr Thurnwald Bernard Struck, Prof. Osborne

1925.12.15 The following were nominated Hon. Fellows: Prof. Dr R. Thurnwald & Dr Marcel Mauss.

1938 HML Une catégorie de l’esprit humain: la notion de personne, celle de ‘moi’: un plan de travail Delivered 29th Nov. at Royal Society

Notes From Elsewhere

Marcel Mauss (French: [mos] mohs; 10 May 1872 – 10 February 1950) was a French sociologist. The nephew of Émile Durkheim, Mauss' academic work traversed the boundaries between sociology and anthropology. Today, he is perhaps better recognised for his influence on the latter discipline, particularly with respect to his analyses of topics such as magic, sacrifice, and gift exchange in different cultures around the world. Mauss had a significant influence upon Claude Lévi-Strauss, the founder of structural anthropology.[1] His most famous book is The Gift (1925).

Mauss was born in Épinal, Vosges, to a Jewish family, and studied philosophy at Bordeaux, where his maternal uncle Émile Durkheim was teaching at the time. He passed the agrégation in 1893. He was also first cousin of the much younger Claudette (née Raphael) Bloch, a marine biologist and mother of Maurice Bloch, who has become a noted anthropologist. Instead of taking the usual route of teaching at a lycée following college, Mauss moved to Paris and took up the study of comparative religion and Sanskrit.

His first publication in 1896 marked the beginning of a prolific career that would produce several landmarks in the sociological literature. Like many members of Année Sociologique, Mauss was attracted to socialism, especially that espoused by Jean Jaurès. He was particularly active in the events of the Dreyfus affair. Towards the end of the century, he helped edit such left-wing papers as Le Populaire, L'Humanité and Le Mouvement socialiste, the last in collaboration with Georges Sorel.

In 1901 Mauss took up a chair in the 'history of religion and uncivilized peoples' at the École pratique des hautes études (EPHE), one of the grandes écoles in Paris. It was at this time that he began drawing more on ethnography, and his work began to develop characteristics now associated with formal anthropology.

The years of World War I were absolutely devastating for Mauss. Many of his friends and colleagues died in the war, and his uncle Durkheim died shortly before its end. Politically, the postwar years were also difficult for Mauss. Durkheim had made changes to school curricula across France, and after his death a backlash against his students began.

Like many other followers of Durkheim, Mauss took refuge in administration. He secured Durkheim's legacy by founding institutions to carry out directions of research, such as l'Institut Français de Sociologie (1924) and l'Institut d'Ethnologie in 1926. Among students he influenced was George Devereux, later an influential anthropologist who combined ethnology with psychoanalysis.

In 1931 Mauss took up the chair of Sociology at the Collège de France. He actively fought against anti-semitism and racial politics both before and after World War II. He died in 1950.

Publications

External Publications

Essai sur la nature et la fonction du sacrifice, (with Henri Hubert) 1898.

La sociologie: objet et méthode, (with Paul Fauconnet) 1901.

De quelques formes primitives de classification, (with Durkheim) 1902.

Esquisse d'une théorie générale de la magie, (with Henri Hubert) 1902.

Essai sur le don, 1925. Les techniques du corps, 1934. [1] Journal de Psychologie 32 (3-4). Reprinted in Mauss,

Sociologie et anthropologie, 1936, Paris: PUF. Sociologie et anthropologie, (selected writings) 1950.

Manuel d'ethnographie. 1967. Editions Payot & Rivages. (Manual of Ethnography 2009. Translated by N. J. Allen. Berghan Books.)