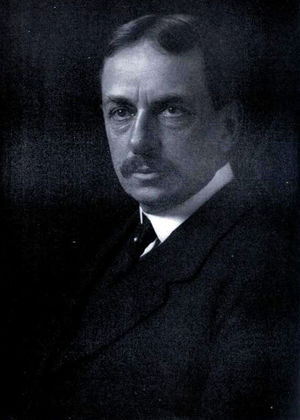

Henry Fairfield Osborn

| Prof. Henry Fairfield Osborn | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Born | 1857 | ||||

| Died | 1935 | ||||

| Occupation |

geologist palaeoethnologist | ||||

| |||||

Contents

Notes

Office Notes

House Notes

1922.11.21 The following were nominated for election as Honorary Fellows (three vacancies) Dr Hugo Obermaier, Dr L. de Vasconcellos, Prof. H. Fairfield Osborne, Dr Paolo Orsi, Dr J.L. Pic, Dr Passits, Dr Hazzodatis

1923.11.20 The following were nominated for election as Honorary Fellows (two vacancies): Prof. H. Fairfield Osborn, Dr Christian, Dr Orsi, Dr Nordenskiold and Prof. Morse

1925.11.17 The following were suggested as Honorary Fellows: Dr Mauss, Dr Thurnwald, Bernard Struck, Prof. Osborne

Notes From Elsewhere

Henry Fairfield Osborn, Sr. ForMemRS[1] (August 8, 1857 – November 6, 1935) was an American geologist, paleontologist, and eugenist, and the president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 years.

Son of the prominent railroad tycoon William Henry and Virginia Reed Osborn, Henry Fairfield Osborn was born in Fairfield, Connecticut, 1857. He studied at Princeton University (1873–1877), obtaining a B.A. in geology and archaeology, where he was mentored by paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope. Two years later, Osborn took a special course of study in anatomy in the College of Physicians and Surgeons and Bellevue Medical School of New York under Dr. William H. Welch, and subsequently studied embryology and comparative anatomy under Thomas Huxley as well as Francis Maitland Balfour at Cambridge University, England.[2][3] In 1880, Osborn obtained a Sc.D. in paleontology from Princeton, becoming a Lecturer in Biology and Professor of Comparative Anatomy from the same university (1883–1890). In 1891, Osborn was hired by Columbia University as a professor of zoology; simultaneously, he accepted a position at the American Museum of Natural History, New York, where he served as the curator of a newly formed Department of Vertebrate Paleontology. As a curator, he assembled a remarkable team of fossil hunters and preparators, including William King Gregory; Roy Chapman Andrews, a possible inspiration for the creation of the fictional archeologist Indiana Jones; and Charles R. Knight, who made murals of dinosaurs in their habitats and sculptures of the living creatures. On November 23, 1897 he was elected member of the Boone and Crockett Club, a wildlife conservation organization founded by Theodore Roosevelt and George Bird Grinnell.[4] Thanks to his considerable family wealth and personal connections, he succeeded Morris K. Jesup as the president of the museum's Board of Trustees in 1908, serving until 1933, during which time he accumulated one of the finest fossil collections in the world.[5] Additionally, Osborn served as President of the New York Zoological Society from 1909 to 1925.

Long a member of the US Geological Survey, Osborn became its senior vertebrate paleontologist in 1924. He led many fossil-hunting expeditions into the American Southwest, starting with his first to Colorado and Wyoming in 1877. Osborn conducted research on Tyrannosaurus brains by cutting open fossilized braincases with a diamond saw.[6] (Modern researchers use computed tomography scans and 3D reconstruction software to visualize the interior of dinosaur endocrania without damaging valuable specimens.)[7] He accumulated a number of prizes for his work in paleontology. In 1901, Osborn was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[8] He described and named Ornitholestes in 1903, Tyrannosaurus rex in 1905, Pentaceratops in 1923, and Velociraptor in 1924. In 1929 Osborn was awarded the Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal from the National Academy of Sciences.[9] Despite his considerable scientific stature during the 1900s and 1910s, Osborn's scientific achievements have not held up well, for they were undermined by ongoing efforts to bend scientific findings to fit his own racist and eugenist viewpoints.

His legacy at the American Museum has proved more enduring. Biographer Ronald Rainger has described Osborn as "a first-rate science administrator and a third-rate scientist."[10] Indeed, Osborn's greatest contributions to science ultimately lay in his efforts to popularize it through visual means. At his urging, staff members at the American Museum of Natural History invested new energy in display, and the museum became one of the pre-eminent sites for exhibition in the early twentieth century as a result. The murals, habitat dioramas, and dinosaur mounts executed during his tenure at the museum attracted millions of visitors, and inspired other museums to imitate his innovations.[11] But his decision to invest heavily in exhibition also alienated certain members of the scientific community and angered curators hoping to spend more time on their own research.[12] Additionally, his efforts to imbue the museum’s exhibits and educational programs with his own racist and eugenist beliefs disturbed many of his contemporaries and have marred his legacy.[13]

Publications

External Publications

From the Greeks to Darwin: An Outline of the Development of the Evolution Idea (1894)

Present Problems in Evolution and Heredity (1892)

Evolution of Mammalian Molar Teeth: To and From the Triangular Type (1907)

Men of the Old Stone Age: Their Environment Life and Art (1915)

The Origin and Evolution of Life (1916)

Men of the Old Stone Age (1916)

The Age of Mammals in Europe, Asia and North America (1921)

Evolution and Religion (1923)

Evolution And Religion In Education (1926)

Man Rises to Parnassus', Critical Epochs in the Pre-History of Man (1927)

Aristogenesis, the Creative Principle in the Origin of Species (1934)