Edward Horace Man

Contents

Notes

Office Notes

House Notes

proposed 1881.01.11

death noted in the Report of the Council for 1929

obit. Man 1930, 9

Notes From Elsewhere

E.H. Man published the first systematic and reliable account of traditional Andamanese life that has stood the test of time. It is today still one of the few standard works on the subject and indispensable to the serious student. He aimed at completeness and came as close to this ideal as was anyone could. His work, titled On the Inhabitants of the Andaman Islands, deals almost exclusively with the two southern, the Aka-Bea and their close relations the Akar-Bale. In Man's day these were the only Andamanese tribes known at all well. Within these limitations Man's book is today still one of the few prime sources on the subject. Happily, the Indians in 1975 have produced a reprint, after the original edition as well as later reprints had become rare and difficult to get hold of. Man's other work on the Nicobarese people is of equal importance in its field.

Given Man's environment, it was by no means natural for an officer to take a friendly interest in the affairs of a primitive, difficult and hostile race. While some of his colleagues muttered under their breath that the best way to deal with the Andamanese was to shoot them, Man actually tried to understand the Negrito and, with only a few slip-ups on the way, succeeded to an astonishing degree. His work remains a testimony to the fact that understanding between cultures and races as far apart as those of Imperial Britain and Paleolithic Negrito is not entirely impossible.

Edward Horace Man was born in Singapore on 13th September 1846 into a family with a strong military background. His mother, Emma Martha Thompson, came from Kentish merchant stock while his father Henry Man was an Andamanese pioneer in his own right.

Edward Horace, therefore, grew up in a family in which the Andamans and Nicobars played a major role. As was customary in those days, the three sons of Captain and Mrs. Man (Edward Horace being the second) were educated in England. Young Edward had wanted to go to sea as a sailor, but at the insistence of his father acquired a commercial training in the City of London. Edward did not find office routine congenial but his later obsessive attention to detail and accuracy owe much to this early training. After six years of life in a London office, the Vice-Roy of India, Lord Mayo, was prevailed upon to appoint young Man assistant to his father at Port Blair. The Vice-Roy agreed on condition that Edward should pass the qualifying examination. This he did with flying colors. E.H. Man arrived at Port Blair in 1869 at the age of 21, working in the Andamans and Nicobars under a series of Superintendents and Chief Commissioners successively as third, second and first assistant and then as Deputy Superintendent until his retirement in 1901. Besides receiving executive functions of increasing importance, E.H. Man also served as district magistrate and was appointed judge in 1894.

E.H. Man collected a vast amount of previously unrecorded information that, without him, would have been lost to science. At the time of his arrival at Port Blair, disease had begun to strike down the Andamanese and an ever increasing number of orphans were left with no one to take care of them. In response to this tragedy Homfray had established an orphanage on Ross island where Andamanese bereft children had found shelter. It was there that Man had his first direct contact with the people that were to become the first of his life's studies. The father had assembled a systematic collection of Andamanese objects which made the solid foundation for his son to build on.

When the younger Man returned from a successful tour of the Nicobar islands in 1875, he was appointed Officer in Charge of the Andamanese. He had won the respect of the Nicobarese by his simplicity and sincerity. The same characteristics would help him establish an immediate rapport with the Andamanese. He immediately set to reforming the Andamanese Home and adapted its practices to reflect the needs of its inmates. At the same time he began to collect information and conduct research into all aspects of traditional Andamanese life. He compiled a 2000-word Aka-Bea vocabulary and worked hard at learning the language. News of his efforts reached Lieutenant R.C. Temple, then studying Burmese in Burma. Temple suggested a system for spelling Andamanese which Man gladly accepted. In 1876 Temple used his official "language leave" to visit the Andamans and a life-long friendship grew up between the two officials. Temple's influence encouraged Man into expanding his linguistic interest. While Temple was inclined to linguistic theory, Man was more a practical collector of facts and figures.

The terrible measles epidemic of 1877 left a lasting mark on the young scientist. With hindsight, we know that this epidemic marked the beginning of the end for the Great Andamanese tribes. With the sick and the dying all over his house and with everybody working to exhaustion on the care of the patients, Man nevertheless forced himself to continue his studies on what in his own estimation was "a very difficult language." Together, Temple and Man published a translation of the Lord's Prayer and completed a grammar of the Aka-Bea language. Unfortunately, the grammar was never published, only a fragment appearing in print in 1878. Man's linguistic progress continued and in 1877 he could write

I am fast learning to chatter to the Andamanese; they are, I think, much surprised at my progress; while preparing the Vocabulary I could not find time to commit to memory many words, and now I am busy collecting words from the tribe on the other side of the Middle Strait [the Akar Bale]

It was Man who had by then discovered that there were eight Great Andamanese tribes (two more would not be discovered until 1900) and that they spoke mutually unintelligible languages. He established friendly relations with all but the Jarawa who, as Man did not realize, were of a different group and made of rather sterner stuff than the Great Andamanese.

In 1879 Man went for a tour of duty to the Nicobars, leaving the Andamanese at the Home in tears. Man's popularity with the Andamanese made the start of his successor, M.V. Portman, a difficult one. From this time onwards there seems to have been a certain amount of tension and mutual dislike between the two men although both were far too gentlemanly to ever openly admit to it. Man was by then widely acknowledged as an authority on matters Andamanese and was soon to be elected member of the Royal Geographical Society, the Royal Anthropological Institute and the Royal Asiatic Society. Portman had similar interests and was about to stake his claim to the same academic territory. That the two men also had totally different characters did nothing to smooth ruffled feelings. The feud can be reconstructed only in vague outline, under layers of false courtesy. The pedantic listing of each others' real or alleged errors of fact provides one hint at the existing tension. It also shows up in the biography written by one of Man's friends for a posthumous reprint of the latter's work on the Nicobarese: Throughout this memoir, Portman is referred to contemptuously as "the successor of Man," never by his name. Man himself would not have been so discourteous and small-minded.

As Elizabeth Edwards of the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford Man's has noted (incidentally supplying one of the extremely rare published quotations from Portman that does not come from one of Portman's own books):

Man's collection of data in both the Andaman Islands and the neighbouring Nicobar Islands appears to have been obsessive. Moseley described him as 'the sort of man who might well send four or five entire Nicobar villages with all the inhabitants inside' (Pitt Rivers Museum, Taylor papers M3). His meticulous and somewhat pedantic recording of native culture appears to have fulfilled some sort of need within him. It was, on the one hand, perhaps the need for recognition and approval from the academic and colonial establishment. This is suggested by his extreme sensitivity to criticism of either his science or his data, as is illustrated by the comments made by M.V. Portman to E.B. Taylor in 1899: Man is very much hurt by the way he thinks I have criticized him ... I adhere to my opinion that much of the Notes on their [the Andamanese] Anthropology is incorrect ... His work is chiefly written on the information of a few boys of different tribes and two convict Jemadars. This is not my idea of accurate scientific research and the results, though good for 1881 will not do for 1899. (Pitt Rivers Museum, Tylor Papers M10)

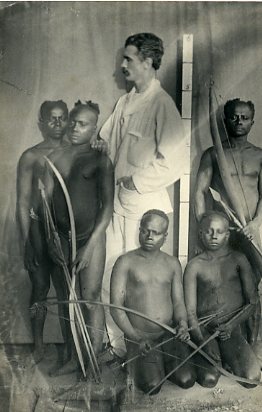

On the other hand, he [Man] clearly needed a sense of power over, affection and deference from and obligation towards the Andamanese in what was, after all, a lonely station. It was also perhaps a response to the predicament in which he found himself as a primary agent in the orchestrated destruction of a culture about which he felt deeply. However, little of this feeling comes across in much of his photography, which is highly structured, clinical and void of the sympathy he is known to have had. Nevertheless, it was this 'scientific' image which was widely disseminated and despite all its shortcomings provided the visual foundation for the anthropological representation of the Andamanese.

Throughout the early 1880s E.H. Man was busy preparing his magnum opus, the Aboriginal Inhabitants of the Andaman Islands. To this work was appended a separate treatise by Man's collaborator, A. J. Ellis, president of the Philological Society, titled Report of Researches into the Language of the South Andaman Island. Ellis also devoted the bulk of his presidential address to his society in London to Man's research. It was remarked that what had started as a labor of love by Man had turned out to be a most important contribution to philological knowledge. The younger Man had found his place in society.

In the following years, he seems to have spent more time in the Nicobars than in the Andamans although it is not clear just how much time and how many tours of duty he did there. His interest in matters Andamanese cooled and this may have had something to do with Portman's success in capturing Andamanese affections.

Further academic honors from gold medals to diplomas followed, along with frequent furloughs to Britain. Speaking engagement followed speaking engagement, British and Continental museums vied with learned societies for the presence of the famous anthropologist and linguist. It was largely thanks to E.H. Man that the Negrito enjoyed a turn of scientific popularity and interest at the turn of the century. The widespread interest helped spur research into other Negrito groups in Malaya and the Philippines as well as into the origin and evolution of the human race generally.

In 1901 Man retired and returned to England where he lived quietly, writing mostly on the Nicobarese and their languages but also publishing his Dictionary of the South Andaman Language as well as lecturing occasionally. He died after a brief illness on 29th September 1929 and lies buried in the little churchyard of Patcham near Brighton.

E.H. Man was an obsessive collector of facts and figures, a highly competent, strictly moral, slightly stiff but not unsympathetic and humane Victorian worthy, a gifted observer and linguist, a pillar of society, who wrote a very important book about the Andamanese, full of scientifically relevant but somehow lifeless facts and figures.

Born Singapore. Served on Andaman and Nicobar Islands, publishing on both.

Commander of the Indian Empire

Publications

External Publications

Aboriginal inhabitants of the Andaman Islands

1975

A dictionary of the central Nicobarese language: English-Nicobarese and Nicobarese-English

House Publications

Related Material Details

RAI Material

papers

photographs

books

Other Material

Brighton Museum

Oxford University Museum

PRM field collector