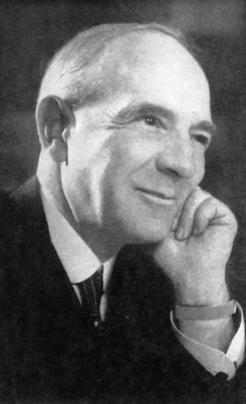

Ernest Jones

Contents

Notes

Office Notes

House Notes

1921.02.22 proposed by W.H.R. Rivers, seconded by A.C. Haddon and F.C. Shrubsall

introduced psychoanalysis to the USA and the UK; founder and editor, International journal of psychoanalysis

1958.02 deceased

1958.03.06 death noted

Notes From Elsewhere

Alfred Ernest Jones FRCP MRCS (1 January 1879 – 11 February 1958) was a Welsh neurologist and psychoanalyst. A lifelong friend and colleague of Sigmund Freud from their first meeting in 1908, he became his official biographer. Jones was the first English-speaking practitioner of psychoanalysis and became its leading exponent in the English-speaking world. As President of both the International Psychoanalytical Association and the British Psycho-Analytical Society in the 1920s and 1930s, Jones exercised a formative influence in the establishment of their organisations, institutions and publications.[1]

Ernest Jones was born in Gowerton (formerly Ffosfelin), Wales, an industrial village on the outskirts of Swansea, the first child of Thomas and Ann Jones. His father was a self-taught colliery engineer who went on to establish himself as a successful business man, becoming accountant and company secretary at the Elba Steelworks in Gowerton. His mother, Mary Ann (née Lewis), was from a Welsh-speaking Carmarthenshire family which had relocated to Swansea.–[2] Jones was educated at Swansea Grammar School, Llandovery College, and Cardiff University in Wales. Jones studied at University College London and meanwhile he obtained the Conjoint diplomas LRCP and MRCS in 1900. A year later, in 1901, he obtained an M.B. degree with honours in medicine and obstetrics. Within five years he received an MD degree and a Membership of the Royal College of Physicians (MRCP) in 1903. He was particularly pleased to receive the University's gold medal in obstetrics from his distinguished fellow-Welshman, Sir John Williams.[3]

After obtaining his medical degrees, Jones specialised in neurology and took a number of posts in London hospitals. It was through his association with the surgeon Wilfred Trotter that Jones first heard of Freud's work. Having worked together as surgeons at University College Hospital, he and Trotter became close friends, with Trotter taking the role of mentor and confidant to his younger colleague. They had in common a wide-ranging interest in philosophy and literature, as well as a growing interest in Continental psychiatric literature and the new forms of clinical therapy it surveyed. By 1905 they were sharing accommodation above Harley Street consulting rooms with Jones's sister, Elizabeth, installed as housekeeper. Trotter and Elizabeth Jones later married. Appalled by the treatment of the mentally ill in institutions, Jones began experimenting with hypnotic techniques in his clinical work.–[4]

Jones first encountered Freud's writings directly in 1905, in a German psychiatric journal in which Freud published the famous Dora case-history. It was thus he formed "the deep impression of there being a man in Vienna who actually listened with attention to every word his patients said to him...a revolutionary difference from the attitude of previous physicians..."–[5]

Jones's early attempts to combine his interest in Freud's ideas with his clinical work with children resulted in adverse effects on his career. In 1906 he was arrested and charged with two counts of indecent assault on two adolescent girls whom he had interviewed in his capacity as an inspector of schools for "mentally defective" children. At the court hearing Jones maintained his innocence, claiming the girls were fantasising about any inappropriate actions by him. The magistrate concluded that no jury would believe the testimony of such children and Jones was acquitted.[a]–[6] In 1908, employed as a pathologist at a London hospital, Jones accepted a colleague’s challenge to demonstrate the repressed sexual memory underlying the hysterical paralysis of a young girl’s arm. Jones duly obliged but, before conducting the interview, he omitted to inform the girl’s consultant or arrange for a chaperone. Subsequently, he faced complaints from the girl’s parents over the nature of the interview and he was forced to resign his hospital post

Jones's first serious relationship was with Loe Kann, a wealthy Dutch émigré referred to him in 1906 after she had become addicted to morphine during treatment for a serious kidney condition. Their relationship lasted until 1913. It ended with Kann in analysis with Freud and Jones, at Freud's behest, undergoing analysis with Sándor Ferenczi.–[8]

A tentative romance with Freud's daughter, Anna, did not survive the disapproval of her father. Before her visit to Britain in the autumn of 1914, which Jones chaperoned, Freud advised him:

She does not claim to be treated as a woman, being still far away from sexual longings and rather refusing man. There is an outspoken understanding between me and her that she should not consider marriage or the preliminaries before she gets 2 or 3 years older.[9]

In 1917 Jones married the Welsh musician Morfydd Llwyn Owen. They were holidaying in South Wales the following year when Morfydd became ill with acute appendicitis. Emergency surgery was carried out at her parents-in-law's Swansea home but Jones and the surgeon who operated were unable to save her from the effects of chloroform poisoning. She was buried in Oystermouth Cemetery on the outskirts of Swansea where her gravestone bears the inscription, chosen by Jones from Goethe's Faust, "Das Unbeschreibliche, hier ist's getan".[b]–[10]

Following some inspired matchmaking by his Viennese colleagues, in 1919 Jones met and married Katherine Jokl, a Jewish economics graduate from Moravia. She had been at school in Vienna with Freud's daughters. They had four children in what proved to be a long and happy marriage, though both struggled to overcome the loss of their eldest child, Gwenith, at the age of 7, during the interwar influenza epidemic.[11] Their son Mervyn Jones became a writer.

Whilst attending a congress of neurologists in Amsterdam in 1907, Jones met Carl Jung, from whom he received a first-hand account of the work of Freud and his circle in Vienna. Confirmed in his judgement of the importance of Freud's work, Jones joined Jung in Zurich to plan the inaugural Psychoanalytical Congress. This was held in 1908 in Salzburg, where Jones met Freud for the first time. Jones travelled to Vienna for further discussions with Freud and introductions to the members of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. Thus began a personal and professional relationship which, to the acknowledged benefit of both, would survive the many dissensions and rivalries which marked the first decades of the psychoanalytic movement, and would last until Freud's death in 1939.[

With his career prospects in Britain in serious difficulty, Jones sought refuge in Canada in 1908. He took up teaching duties in the Department of Psychiatry of the University of Toronto (from 1911, as Associate Professor of Psychiatry). In addition to building a private psychoanalytic practice, he worked as pathologist to the Toronto Asylum and Director of its psychiatric outpatient clinic. Following further meetings with Freud in 1909 at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, where Freud gave a series of lectures on psychoanalysis, and in the Netherlands the following year, Jones set about forging strong working relationships with the nascent American psychoanalytic movement. He gave some 20 papers or addresses to American professional societies at venues ranging from Boston, to Washington and Chicago. In 1910 he co-founded the American Psychopathological Association and the following year the American Psychoanalytic Association, serving as its first Secretary until 1913.[13]

Jones undertook an intensive programme of writing and research, which produced the first of what were to be many significant contributions to psychoanalytic literature, notably monographs on Hamlet and On the Nightmare. A number of these were published in German in the main psychoanalytic periodicals published in Vienna; these secured his status in Freud's inner circle during the period of the latter's increasing estrangement from Jung. In this context in 1912 Jones initiated, with Freud's agreement, the formation of a Committee of loyalists charged with safeguarding the theoretical and institutional legacy of the psychoanalytic movement.[c] This development also served the more immediate purpose of isolating Jung and, with Jones in strategic control, eventually manoeuvring him out of the Presidency of the International Psychoanalytical Association, a post he had held since its inception. When Jung's resignation came in 1914, it was only the outbreak of the Great War that prevented Jones from taking his place.–[14]

Returning to London in 1913, Jones set up in practice as a psychoanalyst, founded the London Psychoanalytic Society, and continued to write and lecture on psychoanalytic theory. A collection of his papers was published as Papers on Psychoanalysis, the first account of psychoanalytic theory and practice by a practising analyst in the English language. .....

After the end of the war, Jones gradually relinquished his many official posts whilst continuing his psychoanalytic practice, writings and lecturing. The major undertaking of his final years was his monumental account of Freud's life and work, published to widespread acclaim in three volumes between 1953 and 1957. In this he was ably assisted by his German-speaking wife, who translated much of Freud's early correspondence and other archive documentation made available by Anna Freud. His uncompleted autobiography, Free Associations, was published posthumously in 1959.

Always proud of his Welsh origins, Jones became a member of the Welsh Nationalist Party, Plaid Cymru. He had a particular love of the Gower Peninsula, which he had explored extensively in his youth. Following the purchase of a holiday cottage in Llanmadoc, this area became a regular holiday retreat for the Jones family. He was instrumental in helping secure its status in 1956, as the first region of the UK to be designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.[23]

Both of Jones's main leisure pursuits resulted in significant publications. A keen ice skater since his schooldays, Jones published an influential textbook on the subject.[24] His passion for chess inspired a psychoanalytical study of the life of American chess genius, Paul Morphy.[25]

Jones was made a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians (FRCP) in 1942, Honorary President of the International Psychoanalytical Association in 1949, and was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Science degree at Swansea University (Wales) in 1954.

Jones died in London on 11 February 1958, and was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium. His ashes were buried in the grave of the oldest of his four children in the churchyard of St Cadoc's Cheriton on the Gower Peninsula.[26]

Publications

External Publications

International journal of psychoanalysis

1912. Papers on Psycho-Analysis. London: Balliere Tindall & Cox. Revised and enlarged editions, 1918, 1923, 1938, 1948 (5th edition).

1920. Treatment of the Neuroses. London: Balliere Tindall & Cox

1921. Psycho-Analysis and the War Neuroses. With Karl Abraham, Sandor Ferenczi and Ernst Simmel. London: International Psycho-Analytical Press

1923. Essays in Applied Psycho-Analysis. London: International Psycho-Analytical Press. Revised and enlarged edition, 1951, London: Hogarth Press. Reprinted (1974) as Psycho-Myth, Psycho-History. 2 vols. New York: Hillstone.

1924 (editor). Social Aspects of Psycho-Analysis: Lectures Delivered under the Auspices of the Sociological Society. London: Williams and Norgate.

1928. Psycho-Analysis. London: E. Benn. Reprinted (1949) with an Addendum as What is Psychoanalysis ?. London: Allen & Unwin.

1931a. On the Nightmare. London: Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

1931b. The Elements of Figure Skating. London: Methuen. Revised and enlarged edition, 1952. London: Allen and Unwin.

1949. Hamlet and Oedipus. London: V. Gollancz.

1953. Sigmund Freud: Life and Work. Vol 1: The Young Freud 1856–1900. London: Hogarth Press.

1955. Sigmund Freud: Life and Work. Vol 2: The Years of Maturity 1901–1919. London: Hogarth Press.

1957. Sigmund Freud: Life and Work. Vol 3: The Last Phase 1919–1939. London: Hogarth Press.

1961. Sigmund Freud: Life and Work. An abridgment of the preceding 3 volume work, by Lionel Trilling and Stephen Marcus, with Introduction by Lionel Trilling. New York: Basic Books.

1956. Sigmund Freud: Four Centenary Addresses. New York: Basic Books

1959. Free Associations: Memories of a Psycho-Analyst. Epilogue by Mervyn Jones. London: Hogarth Press. Reprinted (1990) with a New Introduction by Mervyn Jones. New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers.

House Publications

Related Material Details

RAI Material

Other Material

letters from him to Sigmund Freud in Psychoanalytic electronic publishing