Algernon Charles Swinburne

Algernon Charles Swinburne

Contents

Notes

Office Notes

House Notes

A5 236 J.W. Conrad Cox, Council member, ASL, Lloyds, EC to CCB, 22 Feb. 1866 – acknowledges Swinburne’s letter and cheque; asks CCB to acknowledge them

Notes From Elsewhere

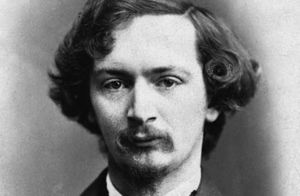

Algernon Charles Swinburne (5 April 1837 – 10 April 1909) was an English poet, playwright, novelist, and critic

Born London; died Putney.

Lyrical Poet, the son of Admiral Charles Henry Swinburne (1797-1877), and Lady Jane Henrietta Ashburnham (1809-1896). Largely raised on the Isle of Wight, he was educated at Eton, but left for reasons now thought to be related to a growing fondness for the flogging inflicted on him there. He was at Balliol College in Oxford from 1856 to 1861, but left without taking a degree. During his time there he had fallen in with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Pre-Raphaelites, but had found the gateway to a much wider circle of influence through an invitation to meet Monckton Milnes some time in May 1861. At one of Milnes’ 10 o’clock breakfasts, on the 5th of June 1861, he was introduced to Burton and the two men took to each other at once.

On the 12th of August 1861 the Burtons and Swinburne were invited to Milnes’ country estate at Fryston in Yorkshire. They were joined by the Parisian Bluestocking Mary Clarke Mohl, Holman Hunt, Francis Turner Palgrave, and the array of emerging and established travellers, artists, political and literary figures that Milnes liked to mix with and bump into each other. This was the first of many Swinburne visits to Fryston, where he developed a habit of staying on long after the other company had left. By this time he had already shown signs of dissipation, a process which was not reversed by his new introductions to Burton, Frederick Hankey, Edward Vaux Bellamy, Colonel John Studholme Hodgson and the rest of the Milnes-Burton coterie. Even though Burton soon left for Fernando Po, he kept in touch with both Swinburne and Milnes, and whenever he returned to London on leave over the coming years, the coterie reunited.

In 1865 Burton induced Swinburne to join the Anthropological Society that he had co-founded two years earlier. With an inner circle of self-styled ‘Cannibals’ they dined together as the at Bertolini’s Hotel[270] near Leicester Square where Swinburne sardonically intoned a Catechism, piously pleading for the roasting, boiling, squeezing and jamming of all the ‘milky, vegetable race’, apostates to the Cannibal Faith:[271]

Preserve us from our enemies,

Thou who art Lord of suns & skies,

Whose meat & drink is flesh in pies

And blood in bowls!

Of thy sweet mercy, damn their eyes,

And damn their souls!

The cannibal of just behaviour

Acknowledges the Lord his saviour,

With gifts of whose especial favour

He hath been crammed,

To whom an offering of sweet savour

Are all the damned.

O Lord, thy people know full well

That all who eat not flesh & fell,

Who cannot rightly speak or spell

Thy various names,

Shall be for ever boiled in hell

Among the flames.

Glad tidings of great exhultation

Proclaim we to the chosen nation;

To all men else in every station

The joyful story

That they are going to damnation

And we to glory.

In pits of sulfur thou wilt cram them,

In chains of burning brimstone jam them,

Squeeze them like figs, like wadding ram them,

With flame surround them;

O Lord of love, confound and damn them

Damn & confound them!

Grind them to pieces small & gritty,

O thou whose names are love & pity!

Roast brown all faces that were pretty,

All black even blacker;

Strip off the trappings of their city,

Paint, plumes, & lacquer.

The foes thy people seek to kill,

Even as a devil do thou grill!

O let thy stormy anger still

Shake them like jellies!

Give thou their carcases to fill

Thy servants’ bellies!

The heathen, whose ungodly lip

Doth in ungodly pewter dip,

Curse his gin, whiskey, rum & flip,

Strong ale & bumbo![272]

Scourge him with anger as a whip

O Mumbo-Jumbo!

The men who eat their neighbours not,

For all such has the Lord made hot

(To boil their souls as in a pot)

The fire of hell:

But if thou leave not me to rot

Then all is well.

The milky, vegetable race

Of such as have not seen thy face,

Lord, damn them by thy special grace

Thou who art gracious.

And raise into the holy place

Me, Athanasius.[273]

A mace was placed on the dinner table, next to the President, in the shape of a negro head in ebony chewing a thigh bone in ivory—Swinburne called it “Ecce Homo”. But Burton was soon off again, in April 1865, to his posting at Santos in Brazil. Swinburne teasingly wrote to his fellow-flagellant Milnes, “As my tempter and favourite audience has gone to Santos I may hope to be a good boy again, after such a ‘jolly good swishing’ as Rodin alone can and dare administer. … The Captain was too many for me; and I may have shaken the thyrsus[274] in your face. But after this half I mean to be no end good.”

Houghton must have said something about dissipation under Burton’s influence, to which Swinburne unflappably responded “As to anything you have fished (how I say not) out of Mrs. Burton to the discredit of my ‘temperance, soberness and chastity’ as the Catechism puts it—how can she who believes in the excellence of ‘Richard’ fail to disbelieve in the virtues of any other man? En moi vous voyez Les Malheurs de la Vertu; en lui Les Prospérités du Vice.[275] In effect it is not given to all his juniors to tenir tête à[276] Burton—but I deny that his hospitality ever succeeded in upsetting me—as he himself on the morrow of a latish séance admitted with approbation, allowing that he had thought to get me off my legs, but my native virtue and circumspection were too much for him.”[277] But as Edmund Gosse remarked, nothing was easier than to get Swinburne “off his legs”.

From Brazil Burton kept up a bantering correspondence with Swinburne (2 letters survive and are given in Volume 2), whose book Poems and Ballads (1866) was attracting increasingly hostile attention: “One anonymous letter from Dublin threatened me, if I did not suppress my book within six weeks from that date, with castration … he had seen his gamekeeper do it with cats.” He promised Burton that “I have in hand a scheme of mixed verse and prose—a sort of etude a la Balzac plus the poetry—which I flatter myself will be more offensive and objectionable to Britannia than anything I have yet done”. Burton replied that “I fairly warn you that at the least sign not of movement retrograde but of remission in advancing you will be bellowed by the British hound”. By now Swinburne had (privately) tired of Monckton Milnes, whose gentle advice about reigning in his drinking he found tedious, and Burton sympathized: “I fear that unless you pall with abject poverty or paralysis you will see no more of our mutual friend Houghton.[278] I hope to arouse his wrath by a Canto of Camões which I have sent to Macmillan”.[279] At the same time Isabel was writing to Houghton asking after “poor little Swinburne,”—“I am sorry for him as far as the drinking propensities go. He is simply possessed by an ‘unclean imp’”.[280]

When Burton returned in 1869 to Europe, en route to his new posting in Damascus, he met up with Swinburne at the end of July for a water cure at Vichy through the month of August. Swinburne may have been looking for a cure for his chronic dysentery. Together Burton and Swinburne tramped over the hilly countryside, returning spent in the evenings to the Hotel de France. They climbed the steep Puy de Dôme, 5000 ft. above sea level, investigated the cathedrals and gathered wild flowers to press. Swinburne, whose mother disapproved of Burton, tried to change her mind with enthusiastic reports home: “I feel now as if I knew for the first time what it was to have an elder brother.” Two weeks after they arrived they were joined by Isabel, and by Adelaide Sartoris, who looked Swinburne up in the hotel register. With Mrs. Sartoris was her close friend Frederick Leighton, and this may have been the first time that Burton met his best-known portrayer. When the month-long water cure was over—“The waters did me some good but I was delighted to leave the hideous hole with its jaundices gout and diabetes. Out of Paris the French are perfect savages”[281]—the Burtons toured the Auvergne with Swinburne. At the end of August they were off overland through Italy to take their boat to the Levant, while Swinburne headed north to drop in on Frederick Hankey and Victor Hugo in Paris, and after that back to England.

In subsequent years Burton would always reunite with Swinburne whenever he was back in London. By 1872, in the long interlude between Burton’s recall from Damascus and his posting in Trieste, Swinburne had already been expelled from the Arts club, either for dancing or for stomping on the hats of other members, depending on who told the story; so they were back at the Cannibal Club—”I shall come and bring my friend (Simeon) Solomon. Yours in the Cannibal Faith, A. C. Swinburne.”[282] The two maintained a steady and affectionate correspondence, and Burton appears often in Swinburne’s letters to others, usually as an exemplar of ruggedness, sometimes as the whole cloth from which to cut a red flag to wave at propriety: “that lost love of Burton’s, the beloved and blue object of his Central African Affections, whose caudal charms and simious seductions were too strong for the narrow laws of Levitical or Mosaic prudery which would confine the jewel of a man to the lotus of a merely human female by the most odious and unnatural of priestly restrictions.”[283]

Monckton Milnes must have complained about Swinburne’s downward spiral to Isabel, who carefully cultivated him—“I don't like Swinburne for neglecting you … I abominate ingratitude”.[284] But as Swinburne later wrote to Burton, he had tired of inoffense—“I got a pathetically pressing invitation to luncheon from our common Houghton. I’m afraid the poor old Thermometer is getting very shaky—but the quicksilver though running low will keep time with the weather to the last.”[285]

Alice “Lallah” Bird left a vivid description of an evening spent in 1878 in the company of the Burtons and Swinburne, at the Welbeck Street house she shared with her brother Dr. George Bird. By then Swinburne was in the closing stages of the alcoholism that he would soon be rescued from by Theodore Watts Dunton, by force—“He looked ill and worn, and older. He had a haggard expression as if his nerves were out of tune. He and Captain Burton were the chief talkers”.[286] Dante Gabriel Rossetti had long given up on him. In 1879 Watts-Dunton removed him to his house The Pines, to be kept on a short leash, prolonged but dampened.

Over the succeeding years there are occasional glints of Swinburne in the company of one or more of the Burtons. Isabel lunched with him in March 1880, introducing him to Lynn Linton, and both Burtons dined with him in the company of the Birds in July 1882. Swinburne later wrote admiringly of Burton’s translation of Camoens’ Lyricks (1884), which was dedicated to him, reciprocating Swinburne’s dedication of his Poems and Ballads Second Series (1878). There was another reunion on Aug. 12, 1885, while the Burtons were in England to arrange the Nights, but that may have been their last meeting.

Swinburne publicly—very bitterly—fell out with Isabel after the death of Burton, specifically over the deathbed conversion act and the destruction of Burton’s manuscripts, attacking her in verse in his ‘Auvergne Elegy’ to Burton.[287] His private sniping was salted with peculiarly old-fashioned anti-popery. He wrote to Theodore Watts-Dunton in July 1891 of “Lady B. or her fellow-conspirators against a deathbed on behalf of the Oly Cartholic Church” and in November 1892 to their former lunch partner Lynn Linton, of “the popish mendacities of that poor liar Lady Burton … she has befouled Richard Burton’s memory like a harpy”.[288]

But it was Swinburne who was Isabel’s “clever friend” who said that Burton projected the “jaw of a Devil and the brow of a God”. And when Edmund Gosse contacted him about writing a precis of Burton’s life ten years after his death (possibly for the DNB) Swinburne could not imagine being that terse, but assured Gosse “from personal experience” that “no more delightful companion can be imagined, either in his most serious or his most humorous moods”.[

Publications

External Publications

Verse drama

· The Queen Mother (1860)

· Rosamond (1860)

· Chastelard (1865)

· Bothwell (1874)

· Mary Stuart (1881)

· Marino Faliero (1885)

· Locrine (1887)

· The Sisters (1892)

· Rosamund, Queen of the Lombards (1899)

Poetry

· Atalanta in Calydon (1865) — [although a tragedy, traditionally included with "Poetry"]

· Poems and Ballads (1866)

· Songs Before Sunrise (1871)

· Songs of Two Nations (1875)

· Erecthus (1876) — [although a tragedy, traditionally included with "Poetry"]

· Poems and Ballads, Second Series (1878)

· Songs of the Springtides (1880)

· Studies in Song (1880)

· The Heptalogia, or the Seven against Sense. A Cap with Seven Bells (1880)

· Tristam of Lyonesse (1882)

· A Century of · Roundels (1883)

· A Midsummer Holiday and Other Poems (1884)

· Poems and Ballads, Third Series (1889)

· Astrophel and Other Poems (1894)

· The Tale of Balen (1896)

· A Channel Passage and Other Poems (1904)

Criticism

· William Blake: A Critical Essay (1868, new edition 1906)

· Under the Microscope (1872)

· George Chapman: A Critical Essay (1875)

· Essays and Studies (1875)

· A Note on Charlotte Brontë (1877)

· A Study of Shakespeare (1880)

· A Study of Victor Hugo (1886)

· A Study of Ben Johnson (1889)

· Studies in Prose and Poetry (1894)

· The Age of Shakespeare (1908)

· Shakespeare (1909)

Major collections

· The poems of Algernon Charles Swinburne, 6 vols. London: Chatto & Windus, 1904.

· The Tragedies of Algernon Charles Swinburne, 5 vols. London: Chatto & Windus, 1905.

· The Complete Works of Algernon Charles Swinburne, ed. Sir Edmund Gosse and Thomas James Wise, 20 vols. Bonchurch Edition; London and New York: William Heinemann and Gabriel Wells, 1925-7.

· The Swinburne Letters, ed. Cecil Y. Lang, 6 vols. 1959-62.