Difference between revisions of "Devonshire"

WikiadminBot (talk | contribs) (Bot: Automated import of articles *** existing text overwritten ***) |

WikiadminBot (talk | contribs) (Bot: Automated import of articles *** existing text overwritten ***) |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

{{Infobox rai-fellow | {{Infobox rai-fellow | ||

| first_name = | | first_name = | ||

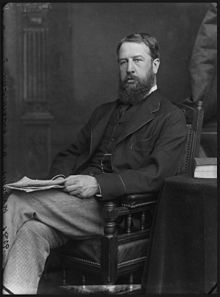

| name = Devonshire | | name = Devonshire | ||

| − | | honorific_prefix = His Grace the Duke of | + | | honorific_prefix = His Grace the Duke of |

| − | | honorific_suffix = | + | | honorific_suffix = |

| image = File:Devonshire,_.jpg | | image = File:Devonshire,_.jpg | ||

| − | | birth_date = | + | | birth_date = 1833 |

| − | | death_date = | + | | death_date = 1908 |

| − | | address = Devonshire House Piccadilly | + | | address = Devonshire House, Piccadilly |

| − | | occupation = aristocracy | + | | occupation = aristocracy |

| − | | elected_ESL = | + | | elected_ESL = |

| elected_ASL = | | elected_ASL = | ||

| − | | elected_AI = | + | | elected_AI = 1892.04.26 |

| elected_APS = | | elected_APS = | ||

| elected_LAS = | | elected_LAS = | ||

| − | | membership = | + | | membership = ordinary fellow |

| − | | left = | + | | left = 1895.10.09 resigned |

| clubs = Athenaeum Club | | clubs = Athenaeum Club | ||

| − | | societies = | + | | societies = |

}} | }} | ||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

| Line 24: | Line 23: | ||

=== House Notes === | === House Notes === | ||

| − | 1892. | + | 1892.03.22 proposed for election at the next meeting |

=== Notes From Elsewhere === | === Notes From Elsewhere === | ||

| − | + | Spencer Compton Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, KG, GCVO, PC, PC (Ire), FRS (23 July 1833 – 24 March 1908), styled Lord Cavendish of Keighley between 1834 and 1858 and Marquess of Hartington between 1858 and 1891, was a British statesman. He has the distinction of having served as leader of three political parties: as Leader of the Liberal Party in the House of Commons (1875–1880) and as of the Liberal Unionist Party (1886–1903) and of the Unionists in the House of Lords (1902–1903) (though the Conservatives and Liberal Unionists operated in close alliance from 1892–1903 and would eventually merge in 1912). He also declined to become Prime Minister on three occasions, not because he was not a serious politician but because the circumstances were never right.<br />Devonshire was the eldest son of William Cavendish, 2nd Earl of Burlington, who succeeded his cousin as Duke of Devonshire in 1858, and Lady Blanche Cavendish (née Howard). Lord Frederick Cavendish and Lord Edward Cavendish were his younger brothers. He was educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he graduated as MA in 1854, having taken a Second in the Mathematical Tripos. He later was made honorary LLD in 1862, and as DCL at Oxford University in 1878.[1]<br /><br />In later life he continued his interests in education as Chancellor of his old university from 1892, and of Manchester University from 1907 until his death. He was Lord Rector of Edinburgh University from 1877 to 1880.After joining the special mission to Russia for Alexander II's accession,[2] Cavendish entered Parliament in the 1857 general election, when he was returned for North Lancashire as a Liberal (his title "Lord Hartington" was a courtesy title; as he was not a peer in his own right he was eligible to sit in the Commons until he succeeded his father as Duke of Devonshire in 1891). Between 1863 and 1874 Hartington held various Government posts, including Civil Lord of the Admiralty and Under-Secretary of State for War under Palmerston and Earl Russell. In the 1868 general election he lost his seat; having refused the Lord Lieutenancy of Ireland, he was made Postmaster-General, without a seat in the Cabinet. The next year he re-entered the Commons, having been returned for Radnor. In 1870 Hartington reluctantly accepted the post of Chief Secretary for Ireland in Gladstone's first government.<br /><br />In 1875 — the year following the Liberal defeat at the General Election — he succeeded William Ewart Gladstone as Leader of the Liberal opposition in the House of Commons after the other serious contender, W. E. Forster, had indicated that he was not interested in the post. The following year, however, Gladstone returned to active political life in the campaign against Turkey's Bulgarian Atrocities. The relative political fortunes of Gladstone and Hartington fluctuated — Gladstone was not popular at the time of Benjamin Disraeli's triumph at the Congress of Berlin, but the Midlothian Campaigns of 1879–80 marked him out as the Liberals' foremost public campaigner.<br /><br />In 1880, after Disraeli's government lost the general election, Hartington was invited by the Queen to form a government, but declined — as did the Earl Granville, Liberal Leader in the House of Lords — after William Ewart Gladstone made it clear that he would not serve under anybody else. Hartington chose instead to serve in Gladstone's Second government as Secretary of State for India (1880–1882) and Secretary of State for War (1882–1885).<br /><br />In 1884 he was instrumental in persuading Gladstone to send a mission to Khartoum for the relief of General Gordon, which arrived two days too late to save him.[3] A considerable number of the Conservative party long held him chiefly responsible for the "betrayal of Gordon." His lethargic manner, apart from his position as war minister, helped to associate him in their minds with a disaster which emphasized the fact that the government acted "too late"; but Gladstone and Lord Granville were no less responsible than he.<br />Hartington became increasingly uneasy with Gladstone's Irish policies, especially after the murder of his younger brother Lord Frederick Cavendish in Phoenix Park. After being elected in December 1885 for the newly created Rossendale Division of Lancashire, he broke with Gladstone altogether. He declined to serve in Gladstone's third government, formed after Gladstone came out in favour of Irish Home Rule (unlike Joseph Chamberlain, who accepted the Local Government Board but then resigned), and after opposing the First Home Rule Bill became the leader of the Liberal Unionists. After the general election of 1886 Hartington declined to become Prime Minister, preferring instead to hold the balance of power in the House of Commons and give support from the back benches to the second Conservative government of the Lord Salisbury. Early in 1887, after the resignation of Lord Randolph Churchill, Salisbury offered to step down and serve in a government under Hartington, who now declined the premiership for the third time. Instead the Liberal Unionist George Goschen accepted the Exchequer in Churchill's place.<br /><br />Having succeeded as Duke of Devonshire in 1891 and entered the House of Lords where, in 1893, he formally moved for the rejection of the Second Home Rule Bill. Devonshire eventually joined Salisbury's third government in 1895 as Lord President of the Council. Devonshire was not asked to become Prime Minister when Lord Salisbury retired in favour of his nephew Arthur Balfour in 1902. He resigned from the government in 1903, and from the Liberal Unionist Association the following spring, in protest at Joseph Chamberlain's Tariff Reform scheme. Devonshire said of Chamberlain's proposals:<br /><br />I venture to express the opinion that [Chamberlain] will find among the projects and plans which he will be called upon to discuss none containing a more Socialistic principle than that which is embodied in his own scheme, which, whether it can properly be described as a scheme of protection or not, is certainly a scheme under which the State is to undertake to regulate the course of commerce and of industry, and tell us where we are to buy, where we are to sell, what commodities we are to manufacture at home, and what we may continue, if we think right, to import from other countries.[5]<br /><br />Balfour, trying to juggle different factions, had allowed both Chamberlain and Free Trade supporters to resign from the government, hoping that Devonshire would remain for the sake of balance, but the latter eventually resigned under pressure from Charles Thomson Ritchie and from his wife, who still hoped that he might lead a government including leading Liberals. But in the autumn of 1907 his health gave way, and grave symptoms of cardiac weakness necessitated his abstaining from public effort and spending the winter abroad. He died, rather suddenly, at Cannes on 24 March 1908<br />He served part-time as Captain in the Duke of Lancaster's Own Yeomanry from 1855 to 1873, and was Honorary Colonel of the 3rd (Militia) Battalion of the Derbyshire Regiment from 1871 and of the 2nd Sussex Artillery Volunteers from 1887.<br />Hartington took great pains to parade his interest in horseracing, so as to cultivate an image of not being entirely obsessed by politics. For many years the courtesan Catherine Walters ("Skittles") was his mistress. He was married at Christ Church, Mayfair, on 16 August 1892, at the age of 59, to Louisa Frederica Augusta von Alten, widow of the late William Drogo Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester. Upon his death, he was succeeded by his nephew Victor Cavendish. He died of pneumonia at the Hotel Metropol in Cannes and was interred on 28 March 1908 at St Peter's Churchyard, Edensor, Derbyshire. A statue of the Duke can be found at the junction of Whitehall and Horse Guards Avenue in London, and also in the Carpet Gardens at Eastbourne<br />Upon receiving news of the Duke's death, the House of Lords took the unprecedented step of adjourning in his honour.[7] Margot Asquith said the Duke of Devonshire "was a man whose like we shall never see again; he stood by himself and could have come from no country in the world but England. He had the figure and appearance of an artisan, with the brevity of a peasant, the courtesy of a king and the noisy sense of humour of a Falstaff. He gave a great, wheezy guffaw at all the right things and was possessed of endless wisdom. He was perfectly disengaged from himself, fearlessly truthful and without pettiness of any kind".[8]<br /><br />Historian Jonathan Parry claimed that "He inherited the whig belief in the duty of political leadership, afforced by the intellectual notions characteristic of well-educated, propertied early to mid-Victorian Liberals: a confidence that the application of free trade, rational public administration, scientific enquiry, and a patriotic defence policy would promote Britain's international greatness—in which he strongly believed—and her economic and social progress...he became a model of the dutiful aristocrat".[9] It has been said that he was "the best excuse that the last half-century has produced for the continuance of the peerages".<br /><br />With 24 years of government service, Devonshire's is the fourth longest ministerial career in modern British politics | |

== Publications == | == Publications == | ||

=== External Publications === | === External Publications === | ||

Latest revision as of 07:26, 22 January 2021

Contents

Notes

Office Notes

House Notes

1892.03.22 proposed for election at the next meeting

Notes From Elsewhere

Spencer Compton Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, KG, GCVO, PC, PC (Ire), FRS (23 July 1833 – 24 March 1908), styled Lord Cavendish of Keighley between 1834 and 1858 and Marquess of Hartington between 1858 and 1891, was a British statesman. He has the distinction of having served as leader of three political parties: as Leader of the Liberal Party in the House of Commons (1875–1880) and as of the Liberal Unionist Party (1886–1903) and of the Unionists in the House of Lords (1902–1903) (though the Conservatives and Liberal Unionists operated in close alliance from 1892–1903 and would eventually merge in 1912). He also declined to become Prime Minister on three occasions, not because he was not a serious politician but because the circumstances were never right.

Devonshire was the eldest son of William Cavendish, 2nd Earl of Burlington, who succeeded his cousin as Duke of Devonshire in 1858, and Lady Blanche Cavendish (née Howard). Lord Frederick Cavendish and Lord Edward Cavendish were his younger brothers. He was educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he graduated as MA in 1854, having taken a Second in the Mathematical Tripos. He later was made honorary LLD in 1862, and as DCL at Oxford University in 1878.[1]

In later life he continued his interests in education as Chancellor of his old university from 1892, and of Manchester University from 1907 until his death. He was Lord Rector of Edinburgh University from 1877 to 1880.After joining the special mission to Russia for Alexander II's accession,[2] Cavendish entered Parliament in the 1857 general election, when he was returned for North Lancashire as a Liberal (his title "Lord Hartington" was a courtesy title; as he was not a peer in his own right he was eligible to sit in the Commons until he succeeded his father as Duke of Devonshire in 1891). Between 1863 and 1874 Hartington held various Government posts, including Civil Lord of the Admiralty and Under-Secretary of State for War under Palmerston and Earl Russell. In the 1868 general election he lost his seat; having refused the Lord Lieutenancy of Ireland, he was made Postmaster-General, without a seat in the Cabinet. The next year he re-entered the Commons, having been returned for Radnor. In 1870 Hartington reluctantly accepted the post of Chief Secretary for Ireland in Gladstone's first government.

In 1875 — the year following the Liberal defeat at the General Election — he succeeded William Ewart Gladstone as Leader of the Liberal opposition in the House of Commons after the other serious contender, W. E. Forster, had indicated that he was not interested in the post. The following year, however, Gladstone returned to active political life in the campaign against Turkey's Bulgarian Atrocities. The relative political fortunes of Gladstone and Hartington fluctuated — Gladstone was not popular at the time of Benjamin Disraeli's triumph at the Congress of Berlin, but the Midlothian Campaigns of 1879–80 marked him out as the Liberals' foremost public campaigner.

In 1880, after Disraeli's government lost the general election, Hartington was invited by the Queen to form a government, but declined — as did the Earl Granville, Liberal Leader in the House of Lords — after William Ewart Gladstone made it clear that he would not serve under anybody else. Hartington chose instead to serve in Gladstone's Second government as Secretary of State for India (1880–1882) and Secretary of State for War (1882–1885).

In 1884 he was instrumental in persuading Gladstone to send a mission to Khartoum for the relief of General Gordon, which arrived two days too late to save him.[3] A considerable number of the Conservative party long held him chiefly responsible for the "betrayal of Gordon." His lethargic manner, apart from his position as war minister, helped to associate him in their minds with a disaster which emphasized the fact that the government acted "too late"; but Gladstone and Lord Granville were no less responsible than he.

Hartington became increasingly uneasy with Gladstone's Irish policies, especially after the murder of his younger brother Lord Frederick Cavendish in Phoenix Park. After being elected in December 1885 for the newly created Rossendale Division of Lancashire, he broke with Gladstone altogether. He declined to serve in Gladstone's third government, formed after Gladstone came out in favour of Irish Home Rule (unlike Joseph Chamberlain, who accepted the Local Government Board but then resigned), and after opposing the First Home Rule Bill became the leader of the Liberal Unionists. After the general election of 1886 Hartington declined to become Prime Minister, preferring instead to hold the balance of power in the House of Commons and give support from the back benches to the second Conservative government of the Lord Salisbury. Early in 1887, after the resignation of Lord Randolph Churchill, Salisbury offered to step down and serve in a government under Hartington, who now declined the premiership for the third time. Instead the Liberal Unionist George Goschen accepted the Exchequer in Churchill's place.

Having succeeded as Duke of Devonshire in 1891 and entered the House of Lords where, in 1893, he formally moved for the rejection of the Second Home Rule Bill. Devonshire eventually joined Salisbury's third government in 1895 as Lord President of the Council. Devonshire was not asked to become Prime Minister when Lord Salisbury retired in favour of his nephew Arthur Balfour in 1902. He resigned from the government in 1903, and from the Liberal Unionist Association the following spring, in protest at Joseph Chamberlain's Tariff Reform scheme. Devonshire said of Chamberlain's proposals:

I venture to express the opinion that [Chamberlain] will find among the projects and plans which he will be called upon to discuss none containing a more Socialistic principle than that which is embodied in his own scheme, which, whether it can properly be described as a scheme of protection or not, is certainly a scheme under which the State is to undertake to regulate the course of commerce and of industry, and tell us where we are to buy, where we are to sell, what commodities we are to manufacture at home, and what we may continue, if we think right, to import from other countries.[5]

Balfour, trying to juggle different factions, had allowed both Chamberlain and Free Trade supporters to resign from the government, hoping that Devonshire would remain for the sake of balance, but the latter eventually resigned under pressure from Charles Thomson Ritchie and from his wife, who still hoped that he might lead a government including leading Liberals. But in the autumn of 1907 his health gave way, and grave symptoms of cardiac weakness necessitated his abstaining from public effort and spending the winter abroad. He died, rather suddenly, at Cannes on 24 March 1908

He served part-time as Captain in the Duke of Lancaster's Own Yeomanry from 1855 to 1873, and was Honorary Colonel of the 3rd (Militia) Battalion of the Derbyshire Regiment from 1871 and of the 2nd Sussex Artillery Volunteers from 1887.

Hartington took great pains to parade his interest in horseracing, so as to cultivate an image of not being entirely obsessed by politics. For many years the courtesan Catherine Walters ("Skittles") was his mistress. He was married at Christ Church, Mayfair, on 16 August 1892, at the age of 59, to Louisa Frederica Augusta von Alten, widow of the late William Drogo Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester. Upon his death, he was succeeded by his nephew Victor Cavendish. He died of pneumonia at the Hotel Metropol in Cannes and was interred on 28 March 1908 at St Peter's Churchyard, Edensor, Derbyshire. A statue of the Duke can be found at the junction of Whitehall and Horse Guards Avenue in London, and also in the Carpet Gardens at Eastbourne

Upon receiving news of the Duke's death, the House of Lords took the unprecedented step of adjourning in his honour.[7] Margot Asquith said the Duke of Devonshire "was a man whose like we shall never see again; he stood by himself and could have come from no country in the world but England. He had the figure and appearance of an artisan, with the brevity of a peasant, the courtesy of a king and the noisy sense of humour of a Falstaff. He gave a great, wheezy guffaw at all the right things and was possessed of endless wisdom. He was perfectly disengaged from himself, fearlessly truthful and without pettiness of any kind".[8]

Historian Jonathan Parry claimed that "He inherited the whig belief in the duty of political leadership, afforced by the intellectual notions characteristic of well-educated, propertied early to mid-Victorian Liberals: a confidence that the application of free trade, rational public administration, scientific enquiry, and a patriotic defence policy would promote Britain's international greatness—in which he strongly believed—and her economic and social progress...he became a model of the dutiful aristocrat".[9] It has been said that he was "the best excuse that the last half-century has produced for the continuance of the peerages".

With 24 years of government service, Devonshire's is the fourth longest ministerial career in modern British politics