Difference between revisions of "John Struthers"

WikiadminBot (talk | contribs) (Bot: Automated import of articles *** existing text overwritten ***) |

WikiadminBot (talk | contribs) (Bot: Automated import of articles *** existing text overwritten ***) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

{{Infobox rai-fellow | {{Infobox rai-fellow | ||

| first_name = John | | first_name = John | ||

Latest revision as of 12:02, 22 January 2021

Contents

Notes

Office Notes

House Notes

proposed 1873.01.21

*assume it is this Struthers - it says Professor Struthers

1892.10.23 proposed for election at next meeting

Notes From Elsewhere

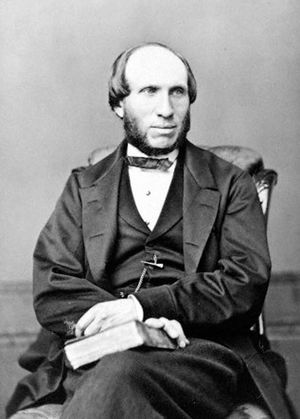

Sir John Struthers (21 February 1823 – 24 February 1899) was the first Regius Professor of Anatomy at the University of Aberdeen. He was a dynamic teacher and administrator, transforming the status of the institutions in which he worked. He was equally passionate about anatomy, enthusiastically seeking out and dissecting the largest and finest specimens, including whales, and troubling his colleagues with his single-minded quest for money and space for his collection.

Among scientists, he is perhaps best known for his work on the ligament which bears his name. His work on the rare and vestigial Ligament of Struthers came to the attention of Charles Darwin, who used it in his Descent of Man to help argue the case that man and other mammals shared a common ancestor.

Among the public, Struthers was famous for his dissection of the "Tay Whale", a humpback whale that appeared in the Firth of Tay, was hunted and then dragged ashore to be exhibited across Britain. Struthers took every opportunity he could to dissect it and recover its bones, and eventually wrote a monograph on it.

In the medical profession, he was known for transforming the teaching of anatomy, for the papers and books that he wrote, as well as for his efficient work in his medical school, for which he was successively awarded medicine's highest honours, including membership of the General Medical Council, fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, the presidency of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, and finally a knighthood

John Struthers was the son of Dr Alexander Struthers (1767–1853) and his wife Mary Reid (1793–1859). They lived in Brucefield, a large stone-built 18th century house with spacious grounds, which was then just outside Dunfermline; John was born in the house.[1] Alexander was a wealthy mill owner and linen merchant. He bought Brucefield early in the 19th century, along with Brucefield Mill, a linen spinning mill built in 1792. Linen was threshed at the nearby threshing mill, and bleached in the open air near the house. There were still linen bleachers living in Brucefield House in 1841, but they had gone by 1851, leaving the house as the seat of the Struthers family.[1] Mary's father, Deacon John Reid, was also a linen maker. Alexander and Mary were married in 1818; the marriage, though not warmly affectionate, lasted until Alexander's death despite the large age difference. Both Alexander and Mary are buried at Dunfermline Abbey.[2]:76

Struthers was one of six children, three boys and three girls. The boys were privately tutored in the classics, mathematics and modern languages at home in Brucefield House. They went out boating in summer, skating in winter on the nearby dam; they rode ponies, went swimming in the nearby Firth of Forth, and went for long walks with wealthy friends.[2]:76 Both his older brother James and his younger brother Alexander studied medicine. James Struthers became a doctor at Leith; Alexander Struthers died of cholera while serving as a doctor in the Crimean War. His sisters Janet and Christina provided a simple education at Brucefield for some poor friends, Daniel and James Thomson. Daniel (1833–1908) became a Dunfermline weaver as well as a historian and reformer.[2]:71

Struthers studied medicine at Edinburgh, winning prizes as an undergraduate. He completed his M.D. degree in 1845, becoming a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh at the same time. In 1847, the college licensed him and his brother James to teach anatomy. The courses that they taught at the medical school in Argyle Square, Edinburgh were recognized by the examining bodies of England, Scotland and Ireland.[2]:77

He worked his way up at the Royal Infirmary from dresser (surgical assistant), to surgical clerk, to house physician, house surgeon and finally full surgeon. His passion was for anatomy; he told the story of how he had been so concentrated on an anatomy dissection one day in 1843 that he failed to look outside to observe the street procession known as the "Disruption" which launched the Free Church of Scotland. He became Lecturer of Anatomy at the University of Edinburgh.[2]:77

From 1860 he was joined by Prof William Pirrie at the university who worked alongside Struthers as Professor of Surgery.[3]

In 1863, Struthers became the first Regius Professor of Anatomy at the University of Aberdeen.[4][5][6] This was a "Crown Chair" (a professorship recognized by the government), a prestigious position. Struthers' application for the chair was supported by over 250 letters, many from public figures including well-known doctors such as Joseph Lister and James Paget, and politicians such as Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, who became Home Secretary, and James Moncreiff, who became the Scottish Lord Advocate.[note 1] The support of these men was actively solicited by Struthers' well-connected friends and relatives, including his cousin the Reverend John Struthers of Prestonpans, and his energetic wife Christina. With the success of their campaign, the family moved to Aberdeen.[2]:77

Struthers held the professorship at Aberdeen for 26 years. In that time, he radically transformed anatomy teaching at the university, improved the Aberdeen medical school; set up the museum of anatomy; and helped to lead the reconstruction of the Aberdeen Infirmary. He vigorously collected specimens for his museum, "prepared or otherwise provided, mainly by the work of my own hands, and at my own expense". The specimens were arranged to enable students to compare the anatomy of different animals. He intended the comparative anatomy exhibits to demonstrate evolution through the presence of homologous structures. For example, in mammals, the arm and hand of a human, the wing of a bird, the foreleg of a horse, and the flipper of a whale are all homologous forelimbs. He continually made demands of the University of Aberdeen's Senate for additional room space and money for the museum, against the wishes of his colleagues in the faculty.[7] Struthers could go to great lengths to obtain specimens he particularly wanted, and on at least one occasion this led to court action. He had long admired a crocodile skeleton at Aberdeen's Medico-Chirurgical Society. In 1866 he borrowed it, ostensibly to clean and remount it, but despite the society's urgent requests to have it returned, it stayed in Struthers' museum at Marischal College for ten years. Struthers still hoped to obtain the specimen, and when in 1885 he was made president of the Medico-Chirurgical Society, he again tried to take the crocodile to his museum. The society then obtained an interdict (a court order) restraining him from removing the skeleton.[8][9]

Struthers published about 70 papers on anatomy. He set up a popular series of lectures for the public, held on Saturday evenings.[2]:78 Many of the methods he used remain relevant today. He had a powerful effect on medical education in Britain, in 1890 establishing the format of three years of "pre-clinical" academic teaching and examination in the sciences underlying medicine, including especially anatomy. His system lasted until the reform of medical training in 1993 and 2003. His 21st century successors at the anatomy school in Aberdeen write that "He would undoubtedly be greatly dismayed at the drastic reduction in the teaching of basic medical sciences, and the subsequent perceived decline in the anatomical knowledge of medical students and practicing clinicians," and they quote one of Struthers' sayings to his students:[8][9]

Unless you are well informed in the foundation sciences and principles, you may practise your profession, but you will never understand disease and its treatment; your practice will be routine, the unintelligent application of the dogmas and directions of your textbook or teacher

Struthers was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree by the University of Glasgow in 1885 for his work in medical education.[2]:78[6] In 1892 he was given honorary membership of the Royal Medical Society; he also became president of the Royal Physical Society of Edinburgh.[2]:78 He was appointed to the General Medical Council in 1883 and remained a member until 1891.[2]:78 He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1894.[11] In 1895 he was made president of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh; he held the position for two years.[2]:78 In 1898, he was knighted (as Sir John Struthers) by Queen Victoria for his service to medicine

.... Struthers' siblings included James Struthers MD (1821-1891), a doctor at Leith hospital for 42 years, and his youngest brother Alexander Struthers MB who died at Scutari in the Crimea.[25]

Struthers married Christina Margaret Alexander (born 15 January 1833) on 5 August 1857. Christina was the sister of John Alexander, chief clerk to Bow Street Police Court. She too came from a Scottish medical family; her parents were Dr James Alexander (1795–1863) and Margaret Finlay (1797-1865), both of old Dunfermline families; James practised as a surgeon just across the English border in the small town of Wooler, Northumberland.[2]:77 On James' death as a "country practitioner", the city-dweller Struthers wrote[26]

The great majority of the profession are and must be country practitioners; the hardest work of the profession is done by them; in the winter nights, when the world is asleep, they have many a long and weary drive; they are far from libraries, from hospitals and museums, and from societies; and thus in their comparative isolation want that stimulus and guidance which tend to keep the city practitioner up to the mark.[26]

Struthers was father-in-law of nitroglycerine chemist David Orme Masson, who married his daughter Mary. He was grandfather of another explosives chemist, Sir James Irvine Orme Masson, and father-in-law of educator Simon Somerville Laurie, who married his daughter Lucy.[27][28]

On retiring from the University of Aberdeen, Struthers returned to Edinburgh. He was buried in the north-east section of the central roundel of Warriston Cemetery, Edinburgh, in 1899; his wife Christina joined him there in 1907. All three of their sons, Alexander, James and John also worked in the medical profession; John followed his father by working at Leith Hospital, then at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary and finally by also becoming president of the Royal College of Surgeons.[2]:79

Publications

External Publications

Struthers, John (1854). Anatomical and Physiological Observations. Edinburgh: Sutherland and Knox.

Struthers, John (1867). Historical Sketch of the Edinburgh Anatomical School. Edinburgh: Maclachlan and Stewart.

Struthers, John (1889). Memoir on the Anatomy of the Humpback Whale, Megaptera Longimana. Edinburgh: Maclachlan.

Struthers, John (1854). "On some points in the abnormal anatomy of the arm". Br. Foreign Medico-Chir. Rev. 13: 523–533.

Struthers, John (1871). "Great Fin Whale". Journal of Anatomical Physiology. 6: 107–125. Struthers, John (1881). "Greenland Right Whale". Journal of Anatomical Physiology. 15: 141–321.

Struthers, John (October 1893). "The New Five-Year Course of Study: Remarks on the position of Anatomy among the Earlier Studies, and on the relative value of Practical Work and of Lectures in Modern Medical Education". Edinburgh Medical Journal.

Struthers, John (1895). "Beluga". Journal of Anatomical Physiology. 30: 124–156.