Difference between revisions of "John (2) Gray"

WikiadminBot (talk | contribs) (Bot: Automated import of articles *** existing text overwritten ***) |

WikiadminBot (talk | contribs) (Bot: Automated import of articles *** existing text overwritten ***) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

{{Infobox rai-fellow | {{Infobox rai-fellow | ||

| first_name = John (2) | | first_name = John (2) | ||

Latest revision as of 08:18, 22 January 2021

Contents

Notes

Office Notes

House Notes

Proposed by J.L. Myres; seconded by A.C. Haddon 1903.01.13

number after name to distinguish from another with same name

Notes From Elsewhere

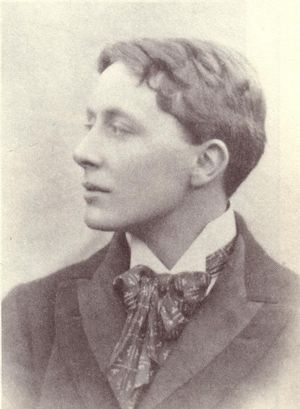

John Gray (2 March 1866 – 14 June 1934) was an English poet whose works include Silverpoints, The Long Road and Park: A Fantastic Story. It has often been suggested that he was the inspiration behind Oscar Wilde's fictional Dorian Gray.

Born in the working-class district of Bethnal Green, London, he was the first of nine children. He left school at the age of 13 and began work as an apprentice metal-worker at the Royal Arsenal.[1] He continued his education by attending a series of evening classes, studying French, German, Latin, music and art. In 1882 he passed the Civil Service exams and, five years later, the University of London matriculation exams. He joined the Foreign Office where he became a librarian.[1]

Gray is best known today as an aesthetic poet of the 1890s and as a friend of Ernest Dowson, Aubrey Beardsley and Oscar Wilde. He was also a talented translator, bringing works by the French Symbolists Stéphane Mallarmé, Paul Verlaine, Jules Laforgue and Arthur Rimbaud into English, often for the first time. He is purported to be the inspiration behind the title character in Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray, but distanced himself from this rumour.[2] In fact, Wilde's story was serialised in Lippincott's Monthly Magazine a year before their relationship began. His relationship with Wilde was initially intense, but had cooled for over two years by the time of Wilde's imprisonment. The relationship appears to have been at its height in the period 1891-1893.[1]

Gray's first notable publication was a collection of verse called Silverpoints (1893), consisting of sixteen original poems and thirteen translations from Verlaine (7), Mallarmé (1), Rimbaud (2), and Baudelaire (3). In his review of it Richard Le Gallienne distinguished it from the output of many of the 'decadent' poets in its inability to accomplish "that gloating abstraction from the larger life of humanity that marks the decadent".[1] Gray's second volume, Spiritual Poems, chiefly done out of several languages (1896), defined his developing identity as a Catholic aesthete. It contained eleven original poems and twenty-nine translations from Jacopone da Todi, Prudentius, Verlaine, Angelus Silesius, Notker Balbulus, St John of the Cross, and other poets both Catholic and Protestant. Gray's later works were mainly devotional and often dealt with various Christian saints. The Long Road (1926) contained his best-known poem, "The Flying Fish", an allegory which had first appeared in The Dial in 1896. Gray produced one novel, Park: A Fantastic Story (1932), a surreal futuristic allegory about Fr Mungo Park, a priest who, in a dream, wakes up in a Britain which has become a post-industrial paradise inhabited by black people who are all Catholics, with the degenerate descendants of the white population living below ground like rats. The novel is characterised by a vein of dry humour, as when a Dominican prior wonders if Park could have met Aquinas. Gray's collected poems, with extensive notes, were printed in a 1988 volume edited by English professor and 1890s expert Ian Fletcher. His definitive biography was published in 1991 by Jerusha Hull McCormack, who also edited a selection of his prose works. McCormack published a fictionalized version of his life in 2000, under the title of "The Man Who Was Dorian Gray". "The Picture of John Gray" by C.J. Wilmann, a play based on John Gray's life, premiered at The Old Red Lion Theatre, London, in August 2014.[3]

Like many of the artists of that period, Gray was a convert to Roman Catholicism. He was baptised on 14 February 1890, but soon lapsed. Wilde's trial appears to have prompted some intense soul-searching in Gray and he re-embraced Catholicism in 1895.[1] In 1896 he gave this reversion poetic form in his volume Spiritual Poems: chiefly done out of several languages. He left his position at the Foreign Office and on 28 November 1898, at the age of 32, he entered the Scots College, Rome, to study for the priesthood. He was ordained by Cardinal Pietro Respighi at St John Lateran on 21 December 1901.[4] He served as a priest in Edinburgh, first at Saint Patrick's and then as rector at Saint Peter's.

His most important supporter, and life partner, was Marc-André Raffalovich, a wealthy poet and early defender of homosexuality. Raffalovich himself became a Catholic in 1896 and joined the tertiary order of Dominicans. When Gray went to Edinburgh he settled nearby. He helped finance St Peter's Church in Morningside where Gray would serve as priest for the rest of his life.[1] The two maintained a chaste relationship until Raffalovich's sudden death in 1934. A devastated Gray died exactly four months later at St. Raphael's nursing home in Edinburgh after a short illness.

The critic Valentine Cunningham has described Gray as the "stereotypical poet of the nineties".[1]

His great-nephew is the alternative rock musician Crispin Gray.

[from The Herald Scotland 29 Nov. 2000]. The Edinburgh priest John Gray is thought to have been the model for Oscar Wilde's debauched

character Dorian Gray. A century after Wilde's death, Marian Pallister finds the debate still raging

ONE hundred years ago today, Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde was lying in extremis at the Hotel d'Alsace, 13 Beaux-Arts, Paris. Cuthbert Dunne, the parish priest, conditionally baptised him and the following day had to give him the sacrament of extreme unction.

The death of the literary genius did not, of course, still the wagging tongues.

Those whose lives he had touched during his 46 years continued to be the focus of gossip and a century has not erased prurient interest in his associates, friends, and putative lovers.

The publication of The Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde, edited by his grandson, Merlin Holland, and Sir Rupert Hart-Davis, has once more raised questions about Canon John Gray, despite 30 exemplary years as a priest in Edinburgh after his friendship with Wilde finished.

Is it true, as the gossips of the day had it, that Canon Gray served as a model for Dorian Gray, the debauched Wildean character who traded his soul to retain his youthful beauty?

Gray was undoubtedly a beautiful young man and one of Wilde's acolytes in the giddy days of the early 1890s. A writer of poetry and short stories, he impressed Wilde enough to put in motion the publication of his first book, Silverpoint.

He was also vain enough (silly enough?) to sign letters as Dorian Gray for some time after Wilde's novel was published in 1890.

Then scandal rocked the hedonistic Wildean coterie: the accusations against Wilde of homo- sexuality; the trial; the sojourn in Reading gaol; the exile to Paris.

Gray put physical and spiritual distance between himself and his former friend by becoming a priest in Scotland.

It wasn't quite far enough.

Andre Raffalovich, son of wealthy Russian Jews who had fled to Paris from Russia, had also been part of the Wilde set. He had quarrelled with Wilde but became Gray's lifelong friend.

He followed Gray to Edinburgh, and not only set up a literary salon there but financed the building of one of Edinburgh's most fascinating churches: one of the rare instances of a Catholic church being funded by one man for another. St Peter's in Morningside was built expressly for his friend, Father John Gray.

The rumours about Gray's private life therefore rumbled on around the douce Edinburgh suburb, but his parishioners held him in great affection and continued to revere his memory for decades after his death in 1934.

Today, 66 years after Gray's death, to ask questions about Canon Gray still raises hackles and engenders debate.

Was his path chosen through altruism, or simply to distance himself from Wilde? The contemporary legislation surrounding homosexuality was harsh. Had enough dirty linen been rinsed through in the 1890s, Wilde might have found Reading gaol too crowded with his associates for comfort.

And who was John Gray anyway? Some toff who caught Wilde's eye as Lord Alfred Douglas would later? In fact, he came from a very different social background. Gray was born in Woolwich in 1866, the eldest of nine children. His father was a carpenter in the dockyard.

A scholarship to Roan Grammar School in Greenwich wasn't enough for the family to be able to afford to keep him at school and he left at 13. His first job was as a metal worker at Woolwich arsenal.

He bridged the vast gulf between manual labour and pinkies cocked around bone china tea cups in the literary salons by going to night school, learning French and Latin, passing the civil service exams, and matriculating at London University. This paid off with a job at the Foreign Office as librarian.

Isobel Murray, Wildean scholar at Aberdeen University, says that Gray was very, very good looking. Florence Gribbell, a member of the Raffalovich family entourage who later became Andre Raffalovich's housekeeper and mistress of his Edinburgh salons, saw Gray for the first time through her opera glasses at the Royal Opera in Covent Garden and said: What a fascinating man. I never knew that anybody could be so beautiful.

He was a dandy, a poet, and his beauty and talent gained him entry to the rarefied circles in which Wilde moved. George Bernard Shaw described him as one of Wilde's more abject disciples to whom Wilde took a lofty attitude. Gray lent weight to the description by inscribing a copy of his translations of Paul Bouget's stories to Wilde as my beloved master and my friend.

It was just too easy for contemporaries at the Rhymers Club to make the Dorian Gray connections in 1891.

A year later, however, he was suing the Star newspaper for suggesting that Mr John Gray . . . is said to be the original Dorian of the same name.

The matter was settled out of court. Then an uncharacteristically clumsy letter from Wilde appeared in the Telegraph disclaiming that paper's assertion that Gray was his protege. Did Gray persuade him to write it?

There was now open speculation about Wilde's sexual orientation. It was particularly dangerous for our man in the Foreign Office to be too closely linked. In 1893, the intense two-year friendship between Wilde and Gray was over. Gray had converted to Catholicism after a trip to Brittany, haunt of back-to-nature Fauvist artists. In 1898, he resigned from the Foreign Office and went to study in Rome.

When he returned a priest, the Bishop of London wouldn't have this former member of Wilde's set in his diocese, which is why the former intellectual dandy was called on to mediate in tenement rammies as a Cowgate curate.

Enter once more Andre Raffalovich, reputed to have broken up the Wilde-Gray friendship to avenge being the butt of one of Wilde's witticisms. Wilde was reported as saying of Raffalovich: He came to London to found a salon and only succeeded in founding a saloon.

Raffalovich now set up house in Whitehouse Terrace, Edinburgh, with Mrs Gribbell as housekeeper, and financed the building of St Peter's on a piece of land which was then a market garden on the Falcon estate.

One of the church's features is a hidden gallery with an entrance from the priest's house from which VIPs could witness the mass. Those VIPs may have included Henry James, Max Beerbohm, and Compton Mackenzie, just some of the guests at 9 Whitehouse Terrace.

Raffalovich ensured that his friend was very comfortable in the priest's house. The study then looked out across the Pentland hills, and architect Sir Robert Lorimer's meticulous attention to detail appeared in the house as well as the church.

When Raffalovich died of a heart attack in 1934, Gray, of course, conducted the funeral service. At the graveside he caught a cold, and within weeks was dead himself. Only the speculation lingered on.

Patricia Napier, whose academic work has chronicled the building of St Peter's and who is now writing a book about Gray and Raffalovich, says: Raffalovich is as important in terms of St Peter's as Gray.

Lorimer, a leading architect of the day, was given a clear design remit. Wildlife motifs and religious symbolism in wrought iron and wood created by Lorimer's craftsmen underscore the simplicity and spirituality of the building.

Stained-glass windows were designed by some of the most outstanding artists of the time, including Morris and Gertrude Meredith Williams. Stark white brick pillars draw the eye to the high altar. Now much changed, this once was a focal point of sea-green Greek marble which the priest approached by steps featuring inlaid fish. The altar rail represented St Peter's fishing net.

Napier says: Gray was the aesthetic guiding light. The ideas of Gray and Raffalovich coincided with those of Lorimer, for whom this was a seminal work.

Only the former baptistry retains the complete sense of symbolism and spirituality which the talented trio achieved within the church. What Napier calls the powerful unity of the stone-faced exterior remains virtually unspoiled.

Despite this legacy, the rumours of early impropriety linger on. Napier says: There are conflicting comments but when you begin to look at that particular accusation you must question the bias of the writers.

Napier adds: I met members of his Cowgate congregation who remembered him as a very committed priest, a powerful intellectual and spiritual mix. His characteristics in later life don't square with the attempted slur on his earlier life.

It is prejudicial thus to suggest that to be gay excludes the ability to be good, but there is perhaps proof from Oscar Wilde himself that Gray was all his Edinburgh parishioners would have liked him to be in those prim pre-Second World War days.

In a bitter letter from Wilde to Lord Alfred Douglas written in the early part of 1897, Wilde says: When I compare my friendship with you to my friendship with such still younger men as John Gray and Pierre Louys I feel ashamed. My real life, my higher life was with them and such as they.

Dorian Gray or a man on a higher plane? Whatever the truth about Gray, his legacy to Scotland is a unique church and an example of priestly devotion.

Publications

External Publications

Silverpoints (1893). Poems

The Blue Calendar (1895–1897). Poems Spiritual Poems, chiefly done out of several languages (1896)

Ad Matrem: Fourteen Scenes in the Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary (1903). Poems

Vivis (1922). Poems

The Long Road (1926). Poems

Poems (1931)

Park: A Fantastic Story (1932). Manchester: Carcanet, 1985. ISBN 0-85635-538-0

The Poems of John Gray (edited by Ian Fletcher). Greensboro, North Carolina: ELT Press, 1988. ISBN 0-944318-00-2

The Selected Prose of John Gray (edited by Jerusha Hull McCormack). Greenboro, North Carolina: ELT Press, 1992. ISBN 0-944318-06-1

House Publications

Some Scottish String Figures. Man

Vol. 3 (1903), pp. 117-118

Related Material Details

RAI Material

photos for Man article

Other Material

Un. of Edinburgh: letters